|

| Col. Nicholson (Alec Guinness) resolves to maintain his men's pride - even at the cost of collaboration! |

Release Date: Oct. 2, 1957. Running Time: 161 minutes. Screenplay: Carl Foreman, Michael Wilson (originally uncredited; credit restored). Based on the novel, The Bridge over the River Kwai, by Pierre Boulle. Producer: Sam Spiegel. Director: David Lean.

THE PLOT:

Commander Shears (William Holden) is a prisoner at a camp in Japanese occupied Thailand. When the extremely English Colonel Nicholson (Alec Guinness) and his men march into camp in perfect formation, Shears regards them with bemusement, fully expecting that he will soon be digging graves for them the same as he has for many of those he was captured with.

Colonel Saito (Sessue Hayakawa), the camp commandant, informs the new arrivals that they will be constructing a bridge over the River Kwai. When he adds that the British officers will work alongside the enlisted men, Nicholson balks, insisting that the Geneva Convention forbids using officers for manual labor. This sets up a contest of wills, with the British officers subjected to intense punishment.

Shears does not wait to see the end of the standoff. He escapes, eventually making his way to Allied territory. Meanwhile, Saito, under increasing pressure to finish the bridge by an unrealistic deadline, accedes to Nicholson's demands.

The bridge now becomes Nicholson's obsession. With the enthusiastic support of his men, he resolves to teach the Japanese "a lesson in Western efficiency that will put them to shame." There's only one problem. Shears has been assigned to help a team of British commandoes. Their mission? To blow up the bridge!

|

| Despite intense punishment, Nicholson refuses to compromise. |

ALEC GUINNESS AS COLONEL NICHOLSON:

Alec Guinness won an Oscar, and he dominates the screen as the proud and stubborn British colonel. One of many memorable moments sees him brought before Saito to try to find a compromise. He is haggard, his skin has a corpse-like pallor, and he has difficulty even walking. Even so, he draws himself up, carrying himself with as much strength as he can muster even though he's on the brink of collapse.

Nicholson is a heroic figure for the movie's first half. Even when he begins proper work on the bridge, he backs up that choice with sound reasoning. He sees that his men have descended into a rabble, and the bridge gives them a task that can be used to restore their sense of self-worth. As the project continues, the project becomes less about British pride and more about his own personal pride, even as his actions hew ever closer to outright collaboration with the enemy.

|

| Shears (William Holden) and the other prisoners observe the conflict between Nicholson and Saito. |

OTHER CHARACTERS:

Commander Shears: The start of the conflict between Nicholson and Saito is filtered through his reactions, which are those of a man who is perfectly happy to swallow his pride if it means he gets to stay alive. When Nicholson insists that the Japanese must be made to understand that they are soldiers and not slaves, Shears counters that he's willing to be "a slave - a living slave." It's not that he's a coward, as the second half shows at several points. He simply has no patience for the kind of romantic, self-satisfied heroics that, in his experience, just end up getting people killed.

Major Warden: The officer in charge of the mission... and he makes one wonder if Apocalypse Now's napalm-loving Kilgore had a British uncle in World War II. Warden plays with explosives with the glee of a child with a toy science kit. He is totally devoted to the mission, valuing its success over the lives of his men, an attitude he justifies all the way through to his final scene. At one point, Shears scornfully compares him to Nicholson, and it's apt as both men take their idea of duty to an extreme that becomes indistinguishable from madness.

Col. Saito: One-time silent movie star Sessue Hayakawa was nominated for a Supporting Actor Oscar as the camp commandant, and he should have won. As great as Alec Guinness is, the test of wills between Nicholson and Saito would be meaningless if Hayakawa didn't provide an equal and opposite presence. Saito is desperate not to lose face by capitulating to Nicholson. He attempts various tactics, from physical punishment to trying to get the enlisted POWs on his side by criticizing the officers' unwillingness to work. When he finally gives in, Nicholson emerges from the "oven" to a hero's welcome from his men... and Saito weeps in private, feeling every ounce of the shame at effectively surrendering to his own prisoner.

Major Clipton: The camp medic, and in many ways the movie's moral center. During the Nicholson/Saito conflict, each colonel tries to appeal to him to get the other to bend, and each describes the other as "mad." Clipton decides they're both mad. Once Nicholson has taken charge of the construction, he's the only British prisoner not persuaded by the project. "Why must we work so well?" he asks, and he is the only one among the British to even try to get Nicholson to see that his actions could be considered collaboration. His is the final face shown in the movie, as he delivers the memorable final lines. Actor James Donald sells all of this perfectly, the lines on his face as important as his voice as he decries the insanity.

|

| Nicholson surveys the (lack of) progress on the bridge. |

THOUGHTS:

"I hate the British! You are defeated, but you have no shame. You are stubborn but have no pride. You endure, but you have no courage!"

-Col. Saito erupts in response to Nicholson's stubbornness.

The Bridge on the River Kwai is often regarded as one of the greatest films of the 1950s, and it's become a mainstay on lists of the best war pictures of all time. It also completely changed the career of director David Lean. Before Kwai, he was a prolific helmer of (mostly excellent) character-based stories, with titles that included: Blithe Spirit, Brief Encounter, Great Expectations, Hobson's Choice, and Summertime. After this movie, all of his films were made on an epic scale - and they became rare events, with him making fewer movies across the rest of his career than he had helmed in the rest of the 1950s alone.

VISUAL STORYTELLING AND INDELIBLE MOMENTS:

When you talk about Bridge on the River Kwai, the first thing that will come to the mind of almost anyone who's watched it is the "Colonel Bogey" scene. Both the current prisoners and the Japanese look on in amazement as Nicholson and his men march into camp in perfect formation while whistling. They take their positions and continue march in place for entire minutes, a defiant show of their spirit.

If that was all there was to the scene, it would be memorable. But Lean also cuts from the spectacle of the march to the feet of the soldiers, showing some men with worn out shoes rotting off their feet and others who are already barefoot. No words are used comment on this, either here or later; the film trusts itself and its audience enough to simply deliver the visual information.

Lean supplies indelible images throughout. When Nicholson refuses to allow himself or his officers to perform manual labor, Saito leaves the defiant officers to stand at attention, baking all day in the harsh sun. Without dialogue, the film dissolves to the glare of the sun beating down on Nicholson, then to a wide shot of the colonel and his officers. What follows is a sustained sequence of the officers standing in place. One finally collapses, and he is left where he falls until the day reaches its end. At that point, the collapsed man is dragged away while the others are sent to even harsher punishment.

The visual storytelling extends to Nicholson's character arc. In the first half of the film, he is frequently seen with his men behind him, culminating in the moment when he wins the contest with Saito and his hoisted onto the shoulders of his subordinates. Even when he shares the screen with Saito, he stands opposite the Japanese colonel, framed as an adversary. By the movie's final Act, however, Nicholson is repeatedly framed with Saito: standing together as they survey the bridge, or walking together under the bridge even as the commando raid reaches its climax. The staging emphasizes what the story has shown: That Nicholson has, however unintentionally, become Saito's ally rather than his enemy.

|

| A reluctant Shears is "volunteered" to join a commando mission. |

MEMORABLE DIALOGUE:

The visual storytelling never comes at the expense of the spoken dialogue. The screenplay was originally credited to the book's author, Pierre Boulle, but in reality it was the work of blacklisted writers Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson. I'll discuss the blacklist issue in a supplemental post. For the purposes of the review, it's enough to note that the script is stuffed with splendid dialogue.

For a movie that's dark in tone, it's surprising how much humor there is. It's dark and cynical humor, offering the release of a chuckle or even a full laugh without breaking the atmosphere. An early scene has Saito telling Nicholson that he will have to commit ritual suicide if he fails to complete the bridge. Nicholson dryly responds: "I suppose if I were you, I'd have to kill myself." This is punctuated brilliantly with Nicholson, who has so far refused Saito's offer of a drink, picking up the glass and offering a gleeful, "Cheers!"

Later, in the other converging storyline, William Holden's Shears finds that he's been "volunteered" to join Major Warden's mission. He is quietly but increasingly alarmed by the major's attitude. The mission involves a parachute drop, something Shears has never been trained for. Warden is utterly unconcerned, telling him to simply "jump and hope for the best." Shears asks: "With or without parachute?" The officers laugh at what they see as a splendid jape, while Shears just looks on with weary resignation.

There are a few splendid monologues: Saito's frustrated eruption at Nicholson, Shears' angry denunciation of treating war as a game, Nicholson's wistful reverie on the completed bridge. All of these are much quoted, and with good reason.

That said, I think my favorite exchange is the tiny character moment that precedes Nicholson's last monologue. Nicholson is standing on the bridge with Col. Saito. The commandant stares up at the sunset and remarks on its beauty. Nicholson, blind to anything other than his monument, believes Saito is referring to the bridge, and Saito does not correct his mistake. Nicholson was made heroic by the first hour, while Saito has unquestionably been the villain... but in this moment, it's Saito who seems the more human of the two.

|

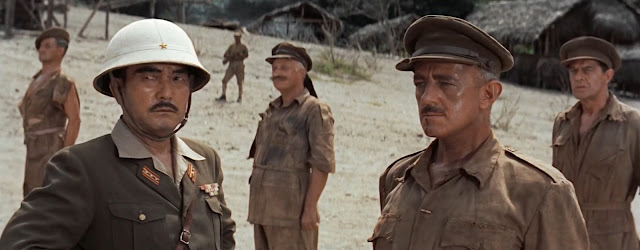

| Two stubborn colonels, one from each side: Saito (Sessue Hayakawa) and Nicholson (Alec Guinness). |

REMAKES AND RETELLINGS:

There has been no direct remake of The Bridge on the River Kwai, though I think it's fair to say that its influence has been felt in many war-themed movies that followed it. The "Colonel Bogey March" has been repeatedly referenced in popular culture. The film itself was directly spoofed by Spike Milligan and Peter Sellers on an LP record, under the title Bridge on the River Wye.

There was also a not-sequel in 1989, Return from the River Kwai. I have not seen it, but it is based on a nonfiction title by Joan and Clay Blair Jr. and is entirely unrelated to David Lean's movie. It drew mixed reviews, and its reception was not helped by its title. Invoking "River Kwai" ended up creating legal problems when the estate of Sam Spiegel, the 1957 film's producer, threatened to sue. The movie went unreleased in the US, and its UK release included a disclaimer that it was unrelated to the earlier picture. Unsurprisingly, and despite a relatively modest budget, it proved to be a financial failure.

|

| Nicholson celebrates the bridge's completion. |

OVERALL:

The Bridge on the River Kwai is a great movie. More importantly from a viewer's standpoint, it's a good movie. This isn't some stolid artwork that viewers must force themselves to endure for The Sake of Technique and/or Message. No, this is a well-paced, thoroughly suspenseful adventure with not a single boring second to its name. Performances are universally excellent, with Alec Guinness and Sessue Haywakawa particularly outstanding, and the movie bristles with energy and life.

I'll close by repeating what I said in my review of Casablanca: If you haven't yet seen this one, watch it; and if you haven't seen it in a while, it might just be worth watching again.

Overall Rating: 10/10.

Related Post: Cracks in the Wall - Marty, The Bridge on the River Kwai, and the Decline of the Hollywood Blacklist

Best Motion Picture - 1956: Around the World in 80 Days

Best Motion Picture - 1958: Gigi

Review Index

To receive new review updates, follow me:

On BlueSky:

On Threads:

No comments:

Post a Comment